Common Elderberry

Common Elderberry

Rita Bober Norm Bober Ken Dahlberg, Chairperson Maynard Kaufman Ron Klein Suzanne Klein Michael Kruk | Jim Laatsch Lisa Phillips, Treasurer Michael Phillips Thom Phillips, Managing Director Jan Ryan, Secretary Jon Towne, Newsletter Editor Dennis Wilcox |

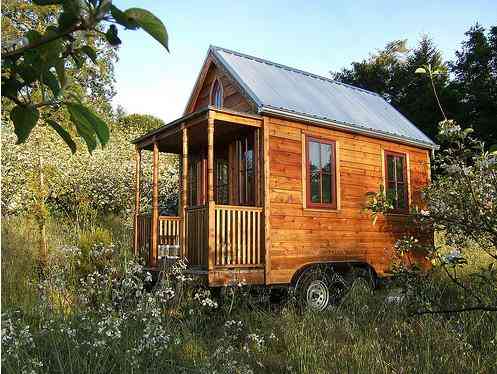

As the recession

disproportionally hits those that historically have had the least

access to resources, I've had to downsize my tiny home aspirations

further. While housing and location has been a cultural investment for

majority groups, for others self-owned housing and property access have

culturally offered the promise of simply being able to exist in this

world. . . .

As the recession

disproportionally hits those that historically have had the least

access to resources, I've had to downsize my tiny home aspirations

further. While housing and location has been a cultural investment for

majority groups, for others self-owned housing and property access have

culturally offered the promise of simply being able to exist in this

world. . . . facilities, rather than each home on the block owning its own tennis court or pool.

facilities, rather than each home on the block owning its own tennis court or pool.  Common Elderberry

Common Elderberry species have

poisonous vegetative parts. For the Common Elderberry, use only

the fruits and flowers. None of the Red elder is usable.

species have

poisonous vegetative parts. For the Common Elderberry, use only

the fruits and flowers. None of the Red elder is usable.