MLT NEWSLETTER

Fall 2012

Cultivating

Resilient Communities

MLT Board of Directors:

|

Rita Bober

Norm Bober

Ken Dahlberg, Chairperson

Maynard Kaufman

Ron Klein

Suzanne Klein

Michael Kruk

|

Jim Laatsch

Lisa Phillips, Treasurer

Michael Phillips

Thom Phillips, Managing Director

Jan Ryan, Secretary

Jon Towne

Dennis Wilcox |

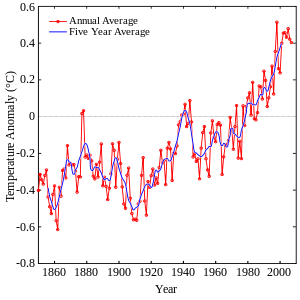

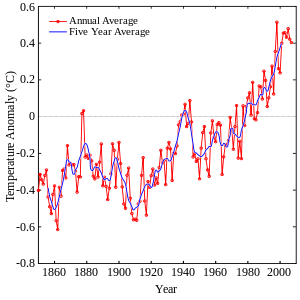

Today,

October 25, we went bicycling in the sunny 80 degree weather. The

leafless trees reminded me of doing the same back in March in similar

80 degree weather. A

period between included a quite severe and

widespread drought.

I'm

not going to

attribute

this warm weather to anything since

I have memories of other “abnormal” weather. I

remember one spring in

1977,

swimming in a warm lake in mid April, I

remember the heat and drought of 1988 which I associate with having

our pond dug that same summer. I don't recall any recent really harsh

winters like the one in the 1980's when Bobbi started getting white

areas on her nose(beginnings of frostbite) while crossing Rainey's

field in -10º

weather. Again,

I'm not going to attribute any

change in weather as

evidence of

global

warming since one person's experience suffers from the criticism of

prejudice

or bias.

But

heat records seem to be broken quite regularly these days.

As

evidenced by

the disappearance of the topic of global

warming

from todays psychotic

(as

in: disassociated from reality) election

“content”(it

has been a campaign topic in every other election since 1988), it

seems like

it's

reality is not

being realized by

the general populace. But that assumption

is again,

just my bias. Jon

Towne

weather. A

period between included a quite severe and

widespread drought.

I'm

not going to

attribute

this warm weather to anything since

I have memories of other “abnormal” weather. I

remember one spring in

1977,

swimming in a warm lake in mid April, I

remember the heat and drought of 1988 which I associate with having

our pond dug that same summer. I don't recall any recent really harsh

winters like the one in the 1980's when Bobbi started getting white

areas on her nose(beginnings of frostbite) while crossing Rainey's

field in -10º

weather. Again,

I'm not going to attribute any

change in weather as

evidence of

global

warming since one person's experience suffers from the criticism of

prejudice

or bias.

But

heat records seem to be broken quite regularly these days.

As

evidenced by

the disappearance of the topic of global

warming

from todays psychotic

(as

in: disassociated from reality) election

“content”(it

has been a campaign topic in every other election since 1988), it

seems like

it's

reality is not

being realized by

the general populace. But that assumption

is again,

just my bias. Jon

Towne

Cattails:

A Wonder of Nature

By

Rita Bober

If you live on or near a lake, you may be familiar with

cattails. They are one of North America’s best known native

plants. Cattails grow on wet ground at or near the wa ter table.

They grow from 5-9 feet tall with all the leaves standing very erect.

The leaves are long and sword-like. The plant has inconspicuous

flowers and later, the hot dog like seed heads which last through the

winter. I recently attended a workshop on cattails and learned a

significant amount of new information about them.

ter table.

They grow from 5-9 feet tall with all the leaves standing very erect.

The leaves are long and sword-like. The plant has inconspicuous

flowers and later, the hot dog like seed heads which last through the

winter. I recently attended a workshop on cattails and learned a

significant amount of new information about them.

Did you know that the Miami People used cattail leaves

to cover their homes and the cattail stems (center core) were used

for doors and room dividers? In the workshop, we practiced making

each of these and realized what a job it was to transform cattails to

these workable products. We also learned to make cordage with the

leaves. Cordage is long, slender, flexible material usually

consisting of several strands (as of thread or yarn) woven or twisted

together similar to rope. In the natural world, cordage can be made

from various plant materials such as cattails leaves, stinging

nettle, dogbane, milkweed stems, as well as the inner bark of

basswood and cedar. This long cord is very strong and can be used

for numerous purposes especially for tying things together; wherever

you would use thread, twine, or rope. Fluff from the seed heads was

used as baby diapers. The mature cattail heads can also be used as

insulation materials for mittens, blankets, and clothing.

Besides all the uses described above, cattails also have

a number of edible qualities. In the spring, the leaf hearts or

shoot cores can be collected from the time the cattail buds begin to

grow until about the middle of summer before the flower stalks are

formed. I have tried these stir-fried in butter as well as pickled.

They were pretty mild tasting but enjoyable. I learned that the

spikes form in the early part of summer make a decent vegetable (only

the top (male) section is used). You can eat them raw or boiled.

They have a taste like corn-on-the-cob and mushroom.

If you leave the spikes alone, they soon develop pollen.

The pollen can be collected and used to make muffins, breads, and

other baked goods (but it must be mixed with wheat flour because it

is not sticky by itself). Make sure to shake it through cheesecloth

or a screen to sift out insects and woolly fibers, and dry before

storing for future use. Cattail flour can be made from the rhizomes.

This involves a labor-intensive process which won’t be described

here. Combined with other flours, it can be used in pancakes,

tortillas, etc.

This plant is also food and shelter to many animals.

Muskrats think the early spring shoots are good food. If you are

investigating a cattail marsh, you may see snapping turtles lurking

in the muddy shallows, mallards raising their young or a great blue

heron looking for anything small enough to swallow. Perhaps you

might even see frogs and snakes.

If you have cattail plants growing in your pond or in a

nearby lake, be sure to take note and begin exploring this

outstanding plant that has many uses and is a valuable edible wild

food source.

Resources:

Identifying

and Harvesting Edible and Medicinal Plants in Wild (and Not So Wild)

Places. “Wild man” Steve

Brill

with Evelyn Dean, 1994, William Morrow and Company, New York, N.Y.

The Forager’s Harvest: A Guide to Identifying,

Harvesting, and Preparing Edible Wild Plants.

Samuel Thayer, 2006, Forager’s Harvest, Ogema, WI.

The Spirit of Healing: A Journal of Plants &

Trees. Osahmin Judith Meister, 2004, Minaden

Books, Hillsboro, WI.

Edited

article originally published in the September 2012 issue of the

Lawton Free Reader.

Lots of

Food Webs and Safety Nets – and Maybe a Few Food Hubs:

Strategic Food System Planning for SW Michigan

By

Ken Dahlberg

Introduction:

Southwest Michigan is a gem in terms of climate, diverse soils,

habitats, crops, towns, cities, ethnic groups, and livelihoods. As

we seek to maintain and enhance this diversity through our work on

regenerative food systems, we need to frame our shorter-term plans

(5-10 years) within the constraints, challenges, and opportunities of

larger and longer-term (20-30 years) threats. Four are crucial in my

view.

Major

long-term threats that require inclusion in strategic food system

design and planning:

I.

Climate Change: A 2009 Union of Concerned Scientists report

summarizes the challenges facing Michigan. It includes some nice

graphics of Michigan “migrating” southwestward over the coming

decades. View at

http://www.ucsusa.org/assets/documents/global_warming/climate-change-michigan.pdf.

II.

Escalating resource and energy costs: General fossil fuel

prices as well as those of the energy- intensive chemical inputs of

industrial agriculture (nitrogen, potassium, and phosphates) will

escalate in the next few decades. Global phosphates reserves are

becoming increasingly depleted and its cost may escalate even more

than other inputs. The environmental costs of industrial as compared

to organic agriculture should also be included in any assessment of

resource and energy costs.

III.

The threats and costs to public health from the overuse of

antibiotics in confined animal facilities (especially “super

bugs” like MRSA) should be assessed along with the threats and

costs to the health of farm soils from the extensive use of GMO

pesticide and herbicide (glyphosate) crop packages. These include

the high costs of trying to control numerous “super weeds” that

have become glyphosate-resistant. Dow Chemical now wants EPA

approval to use for farming a genetically modified soy bean variety

that is resistant to the very dangerous pesticide 2,4-D. This

should be strongly challenged given its clear threats to public

health, the environment, as well as its certain creation of even more

“super weeds.”

IV.

A meltdown of the Palisades nuclear power plant. With the

most brittle containment vessel and the fourth worst safety record in

the U.S., a meltdown would result in a lengthy disaster for the

people of SW Michigan and its rich natural and agricultural heritage.

I would not be at all surprised if the disaster response plans

currently on the shelf are outdated and inadequate at every level,

from the federal on down to the local. The status and adequacy of

these plans should be assessed. For a fascinating review of how

vibrant local food webs and CSAs in Japan significantly helped it

through the earthquake/tsunami, nuclear plant meltdowns, see:

http://blogs.worldwatch.org/nourishingtheplanet/citywatch-japan-earthquake/

Major

evaluative criteria/goals:

I.

Maintain and enhance the health and regenerative capacity of the

region’s living systems at different levels over different time

horizons.

II.

Gradually increase local and regional energy, resource, and economic

self-reliance.

III.

Ensure that legal and regulatory requirements are matched to the

scale of the food webs, safety nets, and hubs that are needed to

achieve the above.

Enhancing

Major Design Concepts:

I.

Food Safety Nets: Examine the various types and how they can be

designed to provide more effective emergency responses; food

security; and the prevention of further declines in public health and

the health of natural systems at all levels from soils on up.

II.

Food Webs: Examine the various natural and socio-natural systems

that provide restorative and regenerative food and ecosystem

services. Whether they have naturally evolved or have been designed,

explore how they provide healthy, diverse, and adaptive communities.

Draw on ecosystem analyses of different trophic levels - from the

level of micro-organisms to habitats, to watersheds and foodsheds, to

biomes, etc.

Also

draw on the work of analysts of socio-natural systems (agroecologists

and anthropologists, for example) exploring the different levels of

human food systems/webs from the field, to the farm, to the

watershed, to foodsheds, to different scale fisheries, to different

type forestry systems, etc.

A soil food web graphic is at:

http://enviroinnovators.com/assets/images/SoilFoodwebDiagram.jpg

A useful article with a good graphic is at:

http://eap.mcgill.ca/MagRack/AJAA/AJAA_4.htm

III.

Food Chains: Conceptually ecologists tend to describe/categorize

these in terms of the flows of energy from primary producers to the

top predators - that is, from one trophic level to the next. There

is a similar flow/level analysis found in the economic concept of

“supply chains.” Sadly, economics does not have a concept

comparable to food webs since they give little attention to

systemic/community relationships - especially informal ones - at any

given level, much less how such relationships interact between

different levels.

Some

Observations on the USDA Regional Food Hub Resource Guide:

Overall,

this is an excellent and encouraging report with lots of substance.

It is available at:

http://www.ams.usda.gov/AMSv1.0/getfile?dDocName=STELPRDC5097957 .

Understandably, there is generous use of terms relating to jobs,

entrepreneurship, etc. There are three concerns that I have - each

of which reflects common cultural assumptions that pose threats to

reaching the full potential of developing regionally adapted - and

adaptive - food safety nets, food webs, and food hubs.

First,

our uncritical acceptance of the “neutrality of technologies”

myth (which somehow leads to “progress”). This acceptance

avoids technology assessments which identify the inevitable

trade-offs and winners and losers associated with new technologies.

No surprise that the Office of Technology Assessment of the US

Congress, which was set up in 1972 to provide Congressional members

and committees with objective and authoritative analyses of the

complex scientific and technical issues, was defunded in 1995 as part

of House Chair Newt Gingrich’s “Contract with America.”

Second,

the minimal awareness of the inevitable trade-offs involved in

“scaling up” (or more rarely, “scaling down”). We fail to

see the parallels with trophic levels in food webs, where the types

of species and their capabilities and limitations change between

trophic levels. With human food webs, “scaling up” beyond a

certain point will risk loss of community by requiring more

standardization and more formalized and hierarchical management.

A

third - and related risk - is that of seeking to expand beyond our

natural boundaries and capacities by seeking “partnerships” with

multi-state and national corporations. Very often, such partnerships

end up with the smaller and weaker partner being co-opted by one of

the many large corporations that dominate our unsustainable

industrial food system. Such co-option reinforces exploitation

rather than encouraging community, sharing and food justice. For

some useful infographics on corporate concentration, see:

https://www.msu.edu/~howardp/infographics.html

Book

Review: The Next American Revolution: Sustainable Activism For The

Twenty-First Century. By

Grace Lee Boggs with Scott Kurashige. University of California

Press, Los Angeles, 2011. By Rita

Bober

In

the late 1960’s and early ‘70’s, Norm and I lived in the city

of Detroit and were involved in the civil rights movement. I don’t

remember hearing about Grace and James Boggs then, though Norm

remembers hearing that they were considered radical. We thought our

ideas were pretty radical but after we moved to Washington, D.C.,

then to southwest Michigan, we weren’t sure what radical meant

anymore. I was delighted to hear of Grace’s new book, The Next

American Revolution. Here are some of my thoughts on its content.

When

the book was published, Grace was 95 years old. Throughout her long

life, she has been influenced by such “humanity-stretching”

movements as the civil rights movement, labor movement, women’s

movement, Black Power movement, Asian American movement, and the

environmental justice movement. These have all influenced her

philosophy of life. In her early years, she was a committed Marxist

but focused more on the human and spiritual contradictions that arise

from a rapidly evolving technology versus the economic stages from

feudalism to capitalism to communism. She reminds us that Marx was

born in 1818. He had not experienced all the human dissonance that

is part of our current reality, a reality that is constantly

changing. “These two notions – that reality is constantly

changing and that you must constantly be aware of the new and more

challenging contradictions that drive change” - is the core of

her thinking.

Another

key to her philosophy is the difference between rebellion and

revolution: “rebellions break the threads that have been holding

the system together. They shake up old values so that relations

between individuals and groups within society are unlikely ever to be

the same again . . . but rebels see themselves and call on others to

see them mainly as victims.” James and Grace came to view

revolutionaries as going “beyond ‘protest politics,’ beyond

just increasing the anger and outrage of the oppressed, and

concentrating instead on projecting and initiating struggles that

involve people at the grassroots in assuming the responsibility for

creating the new values, truths, infrastructures, and institutions

that are necessary to build and govern a new society. Activists

transform and empower themselves when they struggle to change their

reality by exploring, in theory and practice, the potentially

revolutionary social forces of Work, Education, Community,

Citizenship, Patriotism, Health, Justice, and Democracy.” In this

regard, you must believe that humanity can be transformed. Using

Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr. as guides, Grace emphasizes that

we “must become the change we want to see in the world.”

Grace

relates that it is easy to unite against that which we are against.

We need to redirect our focus by defining what we are for

while enacting proposals to govern the whole of society. To do this

we must develop non-antagonistic means to work among ourselves, to

reevaluate our own outmoded concepts and practices in order to create

new energies. Thus, “we must develop our

own capacities for self-government rather than simply demanding and

expecting that our elected representatives take care of us.”

Grace

touches on the changes happening in Detroit, “the

city that was once the national and international symbol of the

miracle of industrialization and is now the national and

international symbol of the devastation of deindustrialization.”

Community building programs; hundreds of home, school, and community

gardens; commercial-size greenhouses; Healthy Kids programs, the

Detroit Agricultural Network and Garden Resource Program, etc. are a

sign that grassroots members of this community are moving to make a

difference. They are taking charge of their own lives and

livelihoods. Numerous articles have been written about the new

emerging Detroit. However, this movement is not only found in

Detroit, but seen in many other urban gardens throughout the United

States. She mentions Will Allen’s Growing Power program in

Milwaukee and Chicago as one initiative. These programs are not only

helping to provide individuals with healthy food, but are striving

for long-term and sustainable transformation of our society. They

are working “to keep our communities, our

environment, and our humanity from being destroyed by corporate

globalization.” The urban agricultural

movement is the fastest growing movement in the United States.

There

is so much covered in this book that I found inspiring. Her concept

of good education, her involvement in the Beloved Communities

Initiative, her own thinking transformed by her involvement in many

movements during her lifetime – all have influenced her approach to

understanding what revolution means. She concludes that the

revolutionary movement in the United States is not headed by a

particular party with a common ideology but by individuals and groups

responding to the real problems and challenges that they face in

their lives and work. The movement is made out of love for people

and for the place where we live. James Boggs shared this thought: “I

love this country, not only because my ancestors’ blood is in the

soil but because of what I believe it can become.” We all need

that belief that the United States can become a better place.

Although I was looking for ideas on how to go about

making “revolutionary” change in my own community, by reading

Grace’s book I began realizing the need to acknowledge the innate

goodness of human beings who have the capability to work

cooperatively for the greater good. In Western civilization we lack

a sense of Spirituality or an awareness of our interconnectedness to

all things. Has our society always been this way? Because we give

priority to economic and technological development over human and

community development, have we lost what it truly means to be a human

being? Grace leads us on a search to find this truth and at the same

time change the way we view “revolution” in our society.

Back to MLT Newsletter Page

weather. A

period between included a quite severe and

widespread drought.

I'm

not going to

attribute

this warm weather to anything since

I have memories of other “abnormal” weather. I

remember one spring in

1977,

swimming in a warm lake in mid April, I

remember the heat and drought of 1988 which I associate with having

our pond dug that same summer. I don't recall any recent really harsh

winters like the one in the 1980's when Bobbi started getting white

areas on her nose(beginnings of frostbite) while crossing Rainey's

field in -10º

weather. Again,

I'm not going to attribute any

change in weather as

evidence of

global

warming since one person's experience suffers from the criticism of

prejudice

or bias.

But

heat records seem to be broken quite regularly these days.

As

evidenced by

the disappearance of the topic of global

warming

from todays psychotic

(as

in: disassociated from reality) election

“content”(it

has been a campaign topic in every other election since 1988), it

seems like

it's

reality is not

being realized by

the general populace. But that assumption

is again,

just my bias. Jon

Towne

weather. A

period between included a quite severe and

widespread drought.

I'm

not going to

attribute

this warm weather to anything since

I have memories of other “abnormal” weather. I

remember one spring in

1977,

swimming in a warm lake in mid April, I

remember the heat and drought of 1988 which I associate with having

our pond dug that same summer. I don't recall any recent really harsh

winters like the one in the 1980's when Bobbi started getting white

areas on her nose(beginnings of frostbite) while crossing Rainey's

field in -10º

weather. Again,

I'm not going to attribute any

change in weather as

evidence of

global

warming since one person's experience suffers from the criticism of

prejudice

or bias.

But

heat records seem to be broken quite regularly these days.

As

evidenced by

the disappearance of the topic of global

warming

from todays psychotic

(as

in: disassociated from reality) election

“content”(it

has been a campaign topic in every other election since 1988), it

seems like

it's

reality is not

being realized by

the general populace. But that assumption

is again,

just my bias. Jon

Towne

ter table.

They grow from 5-9 feet tall with all the leaves standing very erect.

The leaves are long and sword-like. The plant has inconspicuous

flowers and later, the hot dog like seed heads which last through the

winter. I recently attended a workshop on cattails and learned a

significant amount of new information about them.

ter table.

They grow from 5-9 feet tall with all the leaves standing very erect.

The leaves are long and sword-like. The plant has inconspicuous

flowers and later, the hot dog like seed heads which last through the

winter. I recently attended a workshop on cattails and learned a

significant amount of new information about them.