MLT Newsletter

December 1985

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Kenneth Dahlberg

Jan Filonowicz

Albert Huntoon

Maynard Kaufman

Sally Kaufman

Michael Kruk

Lisa Johnson Phillips

Michael Phillips

Thorn Phillips

Mark Thomas

Snow covers the ground bringing beauty, silence, and a kind of repose

until the days lengthen again. The holidays and the beginning of

winter is a time for all of us involved in MLT to give thought to the

efforts we make to overcome the abuses of earth, to bring health and

peace to our world. Happy-and thoughtful-holidays to all of you.

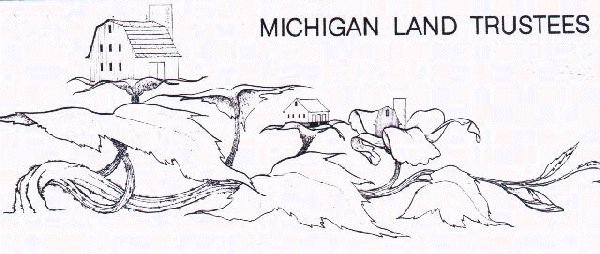

A PERMACULTURE MODEL

-Jonathan Towne-

In the membership renewal flyer of October, 1985, I began a summary of

the Permaculture design course held here in August. I will now

complete that summary by giving a description of the design that the

class began for the homestead farm, subject to some editing by

me. The plan and any other information is available for reading

here at the homestead farm.

The eight members of the class divided into four groups covering:

Buildings and energy; Water; Land use; and Institution. The map

will pinpoint areas of concern while providing additional information.

It was decided that the house needed a greenhouse. There are

three locations eligible with attention drawn to two of them. The

south living room wall could be replaced with glass or the attic room

could be used. This greenhouse would function in plant

propagation, as a drying room and for producing winter food.

A breadbox solar water heater was mentioned as appropriate for

producing household hot water during the warmer seasons. A shed

added on to the barn would protect equipment and house grain cribs and

feed storage.

Conservation of water includes using it as many times as possible and

leaving it on the land as long as possible. Runoff and drainage

are seen as undesirable since the water is under-utilized and results

in erosion and pollution of waterways. Farmstead needs can be met by

roofwater catchments. Zone I irrigation, livestock water, and

household use (except for drinking) can be met this way.

Strategies for the farm land include chiesel plowing for water

retention and ponds to deal with the excess. The ponds can be

constructed cheaply using available equipment. They would add new

dimensions in income potential, providing new edge for fish, ducks and

specialized plants such as basket willows, berries, cattails, bamboos,

etc. They would also function in irrigation and wildlife habitat.

Land utilization around the house would consist of permanently mulched

Zone I gardens of both perennials and annuals. Z.one II would be

similar with an overstory of select tree and shrub crops. A new

windbreak system would protect the house and buildings from the west to

supplement the newly established windbreak to the north of the house.

Further land use strategies include a chicken forage system that would

produce marketable fruits and nuts, and habitat for poultry and,

successionly, pigs. Belts of trees 80-100 feet wide would be

carefully assembled to maximize environmental inputs, light, water and

nutrients, through the use of edge and microclimate. Management would

be by control functions rather than continually wrestling nature to an

early successional stage by annual cropping. Such a system would

be self-maintaining but would require a large initial

expenditure. A productive, complex, stable perennial polyculture

such as this, is an example of a developed permaculture and would be a

model to give to the world.

Out back adjoining the woods, is a sandy-acid area where a specialized

crop, blueberries, could be raised in a polyculture to reduce insect

and bird predation and be self-sustaining in nutrients and water.

Mulch, nitrogen-fixing plants and mulberries would be used to conserve

water, supply nutrients, and reduce predation by birds.

As a transitional strategy, an experimental system growing corn and

soybeans in a clover sod will be done. If possible, a grant will

be procured to finance this. It will require modification of

conventional equipment to till narrow strips, and cattle to stress the

clover. Different techniques and timeing along with different

species of legumes and possible different varieties of corn and

soybeans must be tried to work out a system that is practical.

The farm with these long range experimental programs would be meeting

the institutional needs of MLT. Workshops can be developed around

these activities serving an outreach function. Another design

course can be sponsored in the future. A permaculture design service

can be set up to give workshops and provide designs

for people in this region.

Many details have been left out in this summary. Since

permaculture is concerned with details, this presents a problem which

the reader will have to solve by delving into the subject in more depth.

A

tree

is more

appreciated

when you look

at what trees mean

in your life. There,

in trees you find food,

fuel and shelter. And it's

floors and doors, baskets and

caskets—even rubber gaskets. It's

a handle for the rake, syrup on your

pancake. To the kids it's a great place

to climb from. For some, it's a fascination of

buds and bark, blossoms and form. To others it's

inspiration upon a windswept hill or in a dark, still

valley. To others it's business measured in cords and

board feet. If you ever take a tree for granted, think

about

life

in a

world

with-

out a

tree!

-from Organic Farmer, December 1980

John Yaeger, editor

Michael Petelle, a native of Bangor, who now lives on a small farm in

Fairview, North Carolina, was kind enough to put together the following

thoughts. These are drawn from his Ph. D dissertation and

subsequent publications. Besides the specific points of interest,

there are a couple of larger themes of importance. First, the

piece illustrates how biological/ecological research needs shift

significantly as one moves from monocultures (where the conventional

farmer intervenes and seeks to control the simple systems involved) to

diversified small-scale farming (where the farmer seeks to coordinate

broad crop-animal systems over a longer rotation period) to

permaculture systems (where the designer/horticulturist seeks to

understand and encourage interactions of systems, cycles and levels

over an indefinite period). Second, what this really suggests is that

in permaculture systems a whole new range of ecological interactions

will need to be examined practically and researched scientifically--

an exciting challenge to all of us.

-Ken Dahlberg

.

ON MUTUALISMS

-Michael Petelle-

The obvious and traditional view of herbivory (animal consumption of

plants) is that there is a one-way flow of energy and materials from

the plant to the herbvore. The plant clearly does not benefit

from this relationship. These observations form the basis

for various pest management strategies wherein attempts are made

to prevent insect pests from eating crops.

Mutualisms are interactions between two different types of organisms

where both organisms benefit. Well-known and well-documented mutualisms

exist between ants and aphids and between certain fungi and algae that

form lichens. In these cases and others it is very clear that

there is a mutually beneficial relationship between the associates.

Recently, ecologists have been debating whether or not mutualisms exist

between some herbivores and plants. The notion that herbivores

benefit plants by eating them is certainly counter-intuitive: how

can a plant possibly gain from losing leaf surface area to chewers or

sap to suckers such as aphids? Ecologists have made the

discussion difficult for themselves by demanding that mutualisms be

narrowly defined in terms of reproductive fitness. Measuring

fitness is nearly impossible in many cases. The result is that

ecologists have not been doing much actual research on herbivore/plant

mutualisms.

In agricultural systems reporductive fitness is not an important

concept since it is the farmer who selects which plants survive from

generation to generation. Consequently, it may be easier to study

mutualisms in agroecosystems, because one need not be constrained by a

very narrow definition of mutualism.

An agronomically acceptable definition of an herbivore/plant mutualism

would be: "An herbivore/plant mutualism exists when the plant produces

more 'useful' material at some optimum level of herbivory than when

there is no herbivory at all" (this definition assumes that the

herbivore also benefits from the relationship).

After searching the scientific leterature, it appears that there may be

cases where low levels of herbivory increase crop production. A

few possibilities follow:

1) "Leaf area index" (LAI)

refers to the density of leaves on a plant. Some plants produce too may

leaves - the lower leaves become so shaded that they cannot

photosynthesize. In effect, these leaves are parasitic: they

require sugars to respire but are not producing any sugars for the rest

of the plant. An herbivore chewing holes in leaves can reduce the

LAI enough so that all leaves become productive again. Hence,

crop yields increase.

2) Aphids and other sucking

insects ingest large quantities of sap from plants. Consequently

they excrete large quantities of material called honeydew that is

similar to plant sap. This honeydew may stimulate soil nitrogen

fixation or encourage the growth of beneficial micro-organisms. The

aphids, then, act as a mechanism for transferring sugars, which a plant

can produce in abundance, to micro-organisms which provide nutrients or

disease protection for the plants.

3) Plants transpire water from

their leaves almost continually. Even under dry conditions, they

are losing water. The larger a plant's leaf surface area, the

more water it is losing. Many plants have no mechanism for

dealing with extremely dry conditions. When faced with drought,

such plants have a better chance of survival if they have a small leaf

surface area. Herbivory prior to and during drought

(Herbivory is, in fact, intense during droughts) may remove enough

plant material to allow the plant to survive.

The above are just a few of many mechanisms by which herbivores can

"help" their host plants. Most of the hypothetical mechanisms

discussed in the scientific literature would only be operative over the

long run; they would have little impact on agricultural systems that

are disturbed on a yearly basis. Permaculture systems provide the

long-term stability needed to develop effective mutualisms between

herbivores and plants.

BOOK REVIEW

Maynard Kaufman

Meeting the Expectations of the Land: Essays in Sustainable Agriculture and Stewardship, edited by Wes Jackson, Wendell Berry and Bruce Colman. San Francisco: North Point Press, 1984, 250 pp. $12.50.

Issues related to a sustainable agriculture have been discussed in

several books recently. Most of these have grown out of academic

colloquies. This one was edited and written mainly by

non-academic writers and many of its articles are refreshing for the

breadth of their vision. They reflect the deeper understanding we

have come to expect from creative agricultural thinkers like Wendell

Berry and innovative agricultural researchers like Wes Jackson, who is

working to discover and develop perennial grain crops at The Land

Institute in Kansas.

Like most anthologies, however. Meeting the Expectations of the Land

is a mixed bag, even though we are told that all but two of its

articles were written specifically for this occasion. Wendell

Berry and Wes Jackson and some other contributors to this book

emphasize the fact that sustainable agriculture requires not just

better agronomic techniques but also deeper shifts in cultural values.

Four of the essays extol Amish farming practices and the preface by

Bruce Colman assures us that the example of the Amish can help us meet

the expectations of the land in the creation of a sustainable

agriculture.

Bruce Colman also asserted that "this new agriculture is not a

subsistence oriented, back-to-the-land movement" but that it is a

change in "the commercial, market-oriented, city-supporting agriculture

on which most of us depend." (p.x). This implies reforms in

agricultural practices apart from fundamental changes in the

urban-industrial economy which provides the context of production

agriculture. Some of the articles seem to assume this superficial

reformist position, but it really violates the contention in Wes

Jackson's earlier book (New Roots for Agriculture)

that he and Wendell Berry were concerned about the problem of

agriculture rather than the problems in agriculture. When a

significant percentage of people in a society no longer live on the

land, agriculture emerges to meet their food needs. In our

society much of the food is produced by a farm population which is only

about 3% of the total, something made possible only by the substitution

of fossil fuels for human labor which made the system more

productive. But this development threatens the sustainability of

the food production system because fossil fuels will become scarce and

expensive and because their use has led to agricultural practices which

impact more severely on the ecological system that supports agriculture.

We will eventually have to face up to the possibility that a

sustainable food production system may not be possible within the

context of urban-industrial civilization. Wes Jackson sees this

clearly when he suggests that "sustainability" for both agriculture and

culture will not be achieved in a "high-energy culture" (p. xv).

Jackson explains why in the final chapter of the book. He argues

that there is an inverse relationship between the amount of energy

passing through a system and the amount of biological or cultural

information which sustains it. A large field of corn requires vastly

more fossil fuel energy than the prairie it replaced which was

sustained by its biological information. As farmers simplify an

ecosystem and its biological information degreases they must either put

more energy through the system, as in conventional agribusiness, or

they must substitute their cultural information for the biological

information which was lost, as the Amish farmers, for example, do.

Amish farmers do raise a variety of field, garden and livestock

crops and depend largely on horses for traction power. But their

economic viability is also made possible by the simple, frugal life

which is demanded by their religion as they keep themselves separate

from the world, and by their high degree of self-sufficiency--

production for household use. Both of these factors reduce their

need for large cash incomes, and in these ways the Amish are exemplary

small-scale farmers who embody the cultural information needed for a

sustainable agriculture.

We must conclude that, contrary to Bruce Colman, the new agriculture

will involve a higher proportion of production for subsistence and, if

there are to be more small farms, as most articles in the book propose,

there will have to be a back-to-the-land movement. And, since

Amish religion is intellectually binding and restrictive, it is

fortunate that a voluntary simplicity movement is emerging in other

moral contexts and that production for household use is also

increasing. This latter fact is discussed in Dana Jackson's

contribution to the book, "The Sustainable Garden." The

phenomenon of backyard gardens in America, currently producing crops

roughly equal in value to the corn produced in the vast cornfields of

America, i.e., 15 to 20 billion dollars a year, is probably the least

recognized and most significant movement toward a sustainable

agriculture in our time.

BUSINESS AND OTHER NOTES

A Summary of the 1985 Annual Meeting. Michael Phillips, Secratary, and Mark Thomas, Treasurer:

1. As of November 3, 1985, there is a balance of $1595.75 with

$805 to be disbursed for payments of the drain fee and farm insurance.

2. Committee appointments:

Lease Committee: Swan Huntoon, Jon Towne, Mike Phillips

Permaculture Committee: Jon Towne and Maynard Kaufman

Editorial and Research Committee: Sally Kaufman, Swan Huntoon, MaryAnne Mather, Bobbi Martindale, Ruth Agius.

3. Farm Report: 1986 Needs. Jon Towne and Bobbi Martindale

a. Farm expenditures-Lime, turkey manure, tree seedlings, barn

constrction, elm tree removal, manure spreader and corn planter.

b. Farm house - roof repair, brick work for wood stove, carpeting

for dining room and living room, kitchen floor covering, greenhouse.

c. Books on freshwater aquaculture, wildlife and plants, seeds and woods.

(Editor: if anyone has any of these items he/she would like to donate, especially under the house category of books - agricultural, naturalist, ecological etc., please contact Jon and Bobbi.)

4. Lease Committee. Swan Huntoon recommended the

lease be simplified by eliminating the food inventory and many of the

tools, especially hand tools. The equipment values should be

revised. Jon suggested considering a 5-year lease at the next

meeting.

5. Permaculture Workshop Report. Jon and Bobbi. Plans

for additional workshops must include an increased effort to attract

women. The facilities were too crowded; separate quarters are

needed to house the workshop director. Financial statement: Fees

received $1,620. Expenses $1,790.58. Final cost of the

workshop to MLT $170.58.

6. Future Enterprises: a) Book compiling permaculture

writing; b) MLT brochure; c) Conference on Green politics; d) Spring

country skills workshop; e) Fall permaculture workshop; f) Grant to

facilitate permaculture plans.

Academic stars: Lisa Phillips has returned to school to work on her

master's degree. She was awarded a Western Fellowship for her work in

Earth Science with an emphasis on hydrology. Ken Dahlberg has

three books out within a few months that he has written or

edited. They are Environment and the Global Arena, Natural Resources and People, and New Directions for Agriculture and Agricultural Research.

Thank you for the T shirt orders. I trust by now those of you who

ordered have received your shirts. And for those procrastinators who

have not sent your donations to MLT—start the New Year right and

get the checks in the mail, $5.00 or more per person. Thanks to

all of you who did mail your checks!

The next MLT meeting will be Sunday January 26, at Ken Dahlberg's, 4326

Bronson Boulevard, Kalamazoo. The meeting will be at 3:00 p.m.

followed by a potluck supper at 5:00. All are welcome.

Sally Kaufman, Editor

Return to MLT Newsletter Page