The first four articles are reports on the happenings of 4 groups the MLT has supported recently in the Southwest Michigan area: the Kalamazoo Community Gardens Initiative, the Coop Garden Project of the People's Food Coop in Kalamazoo, and MOFFA's Southwest Michigan Organic Harvest Festival which took place in September 2003 at Tillers Cooks Mill site. Also included is a synopsis of the Greater Grand Rapids Food Systems Council annual report. Closing this newsletter edition is a report on the nearly forgotten eastern hardwood and nut producer, the American Chestnut.

The first is a letter from Kalamazoo Community Gardens initiative which is going on hiatus. We have helped fund them over the last 3 years and consider it money well spent.

To: The Michigan Land Trustees

From: Kalamazoo Community Gardens initiative

Date: January 18, 2004

The Kalamazoo Community Gardens initiative (KCGI) has been active for five years. We have constructed seven community gardens, offered free educational workshops, and raised awareness of the benefits of homegrown vegetables. Throughout the years KCGI has maintained a core group of 5-8 members and worked with many groups and individuals. The organization has been funded by grants and mini-grants from private foundations, individual donations, and fund raising activities. KCGI extends a warm thank you to the Michigan Land Trustees for continuously supporting us with advice, camaraderie and money. Your assistance has been essential for KCGI's survival and will not be forgotten! The 2003 grant was used to pay office rent- having an office was an important step in the right direction toward legitimacy as a non-profit. We thank MLT for aiding KCGI in this endeavor, which was a valuable learning experience.

KCGI has accomplished quite a bit over the years. We have learned much about what it takes to maintain a non-profit organization and felt the challenges of working with many different kinds of people in the Kalamazoo community. After much discussion, in the fall of 2003, the Board of Directors decided that Community Gardens initiative would go on an indefinite hiatus. We have come to realize our efforts will be more effectively channeled when we have a greater appreciation and understanding of the issues and challenges facing the Kalamazoo area and urban gardening as a whole. Within our organizational structure, it was difficult to achieve the goals we set, namely, helping to create community gardens in every neighborhood, especially in low-income areas. We realized that there are many organizational and community-building skills needed to sustain a non-profit that could be learned elsewhere. As individuals we will continue to work on related issues with Fair Food Matters (FFM) and other projects. Tyler Bassett will begin working on a food security inventory in our community; Lucy Bland will begin working on a community incubator kitchen and continue working at the Cooperative Garden; Jenny Doezema will serve on the FFM Schools Gardens committee. When Kalamazoo is ready for a community garden organization in the future, KCGI will be waiting to be picked up again, but for the time being, it is laying fallow!

Co-op Garden Report – 2003 Season

by Chris Dilley

The third season of the Co-op Garden project, a program of the People’s Food Co-op (PFC), was our most successful season yet. The mission of the garden was to be a source of responsibly grown local food and education to our community. The production goals of the garden were funded by the PFC, and served to increase awareness of the PFC and its role in an ever more sustainable local food system. Funding for the educational goals of the project was managed by Fair Food Matters, and came from several sources, including a $500 grant from the Michigan Land Trustees.

The stated educational goals for the season were as follows:

To create an educational opportunity for kids and adults to experience the garden, learning to love and steward the earth and their own bodies

To teach kids and adults to recognize healthful food

To teach the ecological significance of organic, local food and non-motorized transport to the community

To be a source of local produce in season

To actively participate in the local food system

To be a model of an urban, ecological food source

To meet these goals, gardeners Erik Benson and Lucy Bland created and implemented a six-week curriculum. This curriculum integrates the teaching of many aspects of growing food with fun and creative activities and games. Fifteen area youth came out regularly to the garden through relationships with Family & Children Services and Boys & Girls Club. We have received excellent feedback from the youth, their parents and the program coordinators of both organizations.

This season, the children had an area in which they could plant and tend their own vegetables. The children were engaged in projects such as trellising, weeding and watering the main part of the garden as well.

Adult Education:

Through the growing season, more than 25 adult volunteers came to the garden to help with various aspects of the project.

Non-motorized Transportation:

During the second season of the Co-op Garden project, PFC members chipped in to buy a heavy-duty bike trailer that was then used to transport the produce from the garden to the market. This “pedal-powered produce” serves as a way to talk about some of the environmental and human health issues associated with the transnational trucking of much of the food that hits our tables.

Community Awareness:

Information about the program as well as the produce grown by the gardeners was made available at the Bank Street Farmers’ Market and at the People’s Food Co-op this past summer and fall.

What follows is a report of the Sept 2003 Harvest Festival put on by Michigan Food and Farmers Alliance (MOFFA) to which MLT has donated funds over the years. Tillers International (http://www.wmich.edu/tillers/home/), outside of Kalamazoo, has for many years worked towards enhancing international traditional farming practices by incorporating appropriate technologies such as solar and wind to augment draft animals and other native practices as development tools. Tillers is a working farm which disseminates knowledge and skills in about 40 classes a year. Many students go into the Peace Corps, and other international development programs.

Celebrating the Harvest

by Kris Svenson

Sunny autumn skies greeted the first annual Southwest Michigan Organic Harvest Festival at Tillers' Cooks Mill site in September. The inspiration and driving force for the event came from MOFFA (Michigan Organic Food and Farm Alliance). Maynard Kaufman, a member of MOFFA's board, was the organizer. Seven other organizations cooperated in the effort to bring forth the festival: Lake Village Homestead, Lily Hill Farm, Organic Growers of Michigan, People's Food Co-op, Fair Food Matters, Michigan Land Trustees, and Tillers. The Kalamazoo area is the third region in the state in which MOFFA has organized an Organic Harvest Festival. Other festivals have been established in Grand Rapids and Milford.

MOFFA's goal for the festival was to “reintroduce southwest Michigan to local organic and healthy foods and the farmers who nourish our community and earth.” As preparations were make for the celebration, the future site for Tillers artisan village sprung up into a tent village. Huge canopies were set up for a farmer's market, entertainment, educational workshops, food and exhibitor booths, and children's activities.

The day of the harvest festival, volunteers from the cooperating organizations came together at Tillers to make the day a success. It was estimated that between 500 and 700 people came to the event. Organic growers filled the market tent with the abundant fruits of their labors. The atmosphere was kept lively by a series of talented musicians who sang and played throughout the day. Kids did crafty things. Six hours of workshops on various topics like “Why Local Food?”, “Gimme That Ol' Time Nutrition,” and “Organic Pest Management” drew a steady stream of information seekers. A knot of observers hung close around the interns as they demonstrated plowing capabilities of the ox. Many of the festival's visitors took a tour of the farm via horse and wagon. Tillers volunteer, Jim Greenman, brought his team out for the day and volunteered his time to help us show people around.

It

was a day of both new and familiar faces at Tillers. Many

acquaintances and connections were made. MOFFA reached its goal of

bringing people together to celebrate and

learn about local foods and local farmers. We hope that the success

of this festival will be built upon to make the second annual Organic

Harvest Festival even better.

Annual 2002-2003 Report (summarized by Jon Towne)

This group formed in 2001 with the help of some MLT seed money to explore and develop a “more just and sustainable food system in West Michigan”. Their purpose statement is: “To support and promote physical and economic access to sufficient, nutritious food raised in a sustainable manner with an emphasis on local production.” As Tom Cary, GGRFSC Board Chair, further elaborates in this report: “We envision a network of local producers (farmers and gardeners), distributors, processors, chefs, retailers, agencies and residents working together to create a local food system that ensures food security for all, is ecologically and economically sustainable, enhances productive capacity and connects our communities together and to the place in which we live.”

The GGRFSC has begun a baseline assessment of the West Michigan food system, including land use, policies, food distribution, and buying habits. Hopefully they will come up with a plan to realize the potential of developing local sustainable food production and marketing strategies. Some of the projects and accomplishments of the GGRFSC include partnerships supplying key seed money and energy developing community gardens and maximizing this self provisioning potential in Grand Rapids. The GGRFSC helped start The Southeast Community Farmer's Market which operates on Thursdays during the growing season. Realizing that development of local food systems requires education about the present food systems and its destructive effects, education programs are presented to encourage reflection and the realization of better alternatives. Regaining lost skills and knowledge such as food preservation, community gardening, and their effects on nutrition has been or will be the subject of GGRFSC sponsored education events. Much of their emphasis has been on students whether college, high school or elementary age. Continuing with a synopsis of the accomplishments of this well rounded group, is their interest on food security public policy. They worked with the Kent County Emergency Needs Task Force, and formed a partnership with other area agencies on a gleaning program to encourage self provisioning for people in need. The GGRFSC put on a conference “Rooted in Community: Democratizing the Food System” with 100 attendees. They also put out a quarterly newsletter.

This energetic group seems closely aligned with Michigan Land Trustees and I am sure they welcome input and participation. Hopefully this is an albeit incomplete but basically accurate description of this group(apologies to GGRFSC for unintentional mangling!)

Greater Grand Rapids Food Systems Council

C/O West Michigan Environmental Action Council

1514 Wealthy St. SE-Suite 280

Grand Rapids, MI 49506

info@foodshed.net

American Chestnuts: Coming Back?

Jon Towne

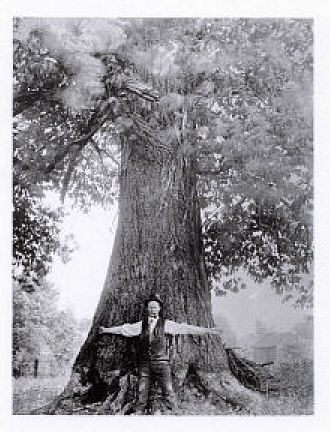

I have been fascinated with this tree since the 1970's when I was shown several blighted specimens in this area. This tree was a dominant tree throughout the Appalachians, with its range extending into Southeastern Michigan, and it appeared to be spreading as of 1900. Estimates are that it made up half of the timber value in the Appalachians at that time. It tended to get very large with a massive trunk providing durable wood useful for just about anything. Some called Castanea dentata “the redwood of the east”, presumably because of its size (10 feet or more in diameter) and rot resistant wood. On top of its useful wood, it produced huge crops of nuts and so was also called the “corn tree”, also since the nuts have a somewhat similar nutritional composition to corn. Livestock were turned into the forests to be fattened by these trees. Cryphonectria

parasitica , a fungus introduced from the Orient on some Chinese

Chestnut logs in New York City, devastated and basically eliminated

this tree from the East over a few short years in the first half of

the 20th century. Only some plantings outside of its native range

have survived where the blight has not reached. This fungus attacks

the tree by destroying the cambium layer faster than the tree can

form callus tissue around it, basically girdling the tree. The trunk

and top subsequently die leaving a viable root system which in many

cases has continued to send up sprouts throughout its range. This

characteristic of leaving the root system intact, could potentially

cause a rapid resurgence of the tree if a degree of immunity could be

applied.

Cryphonectria

parasitica , a fungus introduced from the Orient on some Chinese

Chestnut logs in New York City, devastated and basically eliminated

this tree from the East over a few short years in the first half of

the 20th century. Only some plantings outside of its native range

have survived where the blight has not reached. This fungus attacks

the tree by destroying the cambium layer faster than the tree can

form callus tissue around it, basically girdling the tree. The trunk

and top subsequently die leaving a viable root system which in many

cases has continued to send up sprouts throughout its range. This

characteristic of leaving the root system intact, could potentially

cause a rapid resurgence of the tree if a degree of immunity could be

applied.

med to be surviving the

disease. The fungal disease seemed less

virulent and the tree seemed to heal cankers as they developed. Most

importantly this viral “disease” of the blight

spread easily thus saving the European chestnut industry. More

recently something similar was observed in Michigan, trees were

surviving although in a weakened state. Because of many varieties of

Cryphonectria parasitica in

the US, this virus doesn't appear to spread easily and isn't always

effective. As noted

above, hypovirulence has the potential to quickly restore the

Chestnut to prominence because of the still living root systems. From

what I can see from my reading, it is not believed that this

phenomena will have a significant effect in the near term. The large

tree pictured just east of Bangor, MI apparently has been infected

with the hypovirulent form of the blight since the 1940's.

med to be surviving the

disease. The fungal disease seemed less

virulent and the tree seemed to heal cankers as they developed. Most

importantly this viral “disease” of the blight

spread easily thus saving the European chestnut industry. More

recently something similar was observed in Michigan, trees were

surviving although in a weakened state. Because of many varieties of

Cryphonectria parasitica in

the US, this virus doesn't appear to spread easily and isn't always

effective. As noted

above, hypovirulence has the potential to quickly restore the

Chestnut to prominence because of the still living root systems. From

what I can see from my reading, it is not believed that this

phenomena will have a significant effect in the near term. The large

tree pictured just east of Bangor, MI apparently has been infected

with the hypovirulent form of the blight since the 1940's.

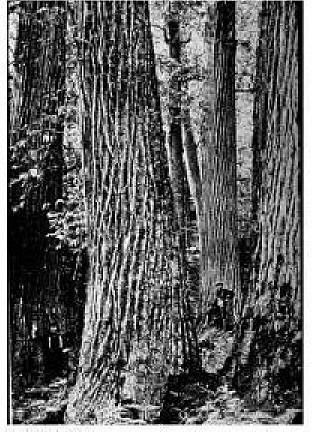

About

1980, I planted some A. Chestnuts on the Land Trust Homesteading

farm. In line with my talent for killing trees by planting them, I

ended up with one tree surviving from that group. It grew well until

about five years ago when I noticed die off with broken up, infected

bark surrounded by the fungus' characteristic reddish fruiting

bodies. The trunk is dead but still sends up sprouts from its base. The

more recent plantings in a couple different locations were more

successful in number of trees produced. One of the groups planted in

the mid 1980's is now infected, a picture of one is included, showing

the characteristic reddish color of the

fruiting bodies of the fungus. I have more recent plantings in the

1990's that so far are uninfected. I don't know if there is any

hypovirulence at work, except that it took 3-4 years for the first

tree to die back to the ground. I have also planted Chinese

Chestnuts but found that they don't do well with my soil conditions

and its preponderance of clay, the americans seem more adaptable to

this soil type. By continuing to plant chestnuts frequently, I hope

(hope is the word) to take advantage of and participate in

species variation and natural selection of the blight, the

hypovirulent strain, and the tree itself to maybe contribute to the

overall gene pool. Who knows!

About

1980, I planted some A. Chestnuts on the Land Trust Homesteading

farm. In line with my talent for killing trees by planting them, I

ended up with one tree surviving from that group. It grew well until

about five years ago when I noticed die off with broken up, infected

bark surrounded by the fungus' characteristic reddish fruiting

bodies. The trunk is dead but still sends up sprouts from its base. The

more recent plantings in a couple different locations were more

successful in number of trees produced. One of the groups planted in

the mid 1980's is now infected, a picture of one is included, showing

the characteristic reddish color of the

fruiting bodies of the fungus. I have more recent plantings in the

1990's that so far are uninfected. I don't know if there is any

hypovirulence at work, except that it took 3-4 years for the first

tree to die back to the ground. I have also planted Chinese

Chestnuts but found that they don't do well with my soil conditions

and its preponderance of clay, the americans seem more adaptable to

this soil type. By continuing to plant chestnuts frequently, I hope

(hope is the word) to take advantage of and participate in

species variation and natural selection of the blight, the

hypovirulent strain, and the tree itself to maybe contribute to the

overall gene pool. Who knows!

On

a side note, in the late 1980's I wrote a proposal for funds from the

State of Michigan Nongame Wildlife Fund to plant an acre of Castanea

dentata for this very purpose under the auspices of MLT.

Unfortunately it didn't happen. But it is comforting to know that

much more serious and thought out planting and breeding work were

getting under way at that time and the result may show itself in the

next few years. After a century long hiatus, the best may yet to be

for this magnificent tree!

On

a side note, in the late 1980's I wrote a proposal for funds from the

State of Michigan Nongame Wildlife Fund to plant an acre of Castanea

dentata for this very purpose under the auspices of MLT.

Unfortunately it didn't happen. But it is comforting to know that

much more serious and thought out planting and breeding work were

getting under way at that time and the result may show itself in the

next few years. After a century long hiatus, the best may yet to be

for this magnificent tree!

| TACF was founded in 1983 by a group of plant biologists with the serious intention of restoring the American Chestnut. They are undertaking the 25 year back cross method of breeding a blight resistant American Chestnut. They produce a journal and have a mailing list. |